October 18th, 2023

Philip Sadler, Remy Dou, Gerhard Sonnert, and Susan Sunbury share more about the Instrument Development: Racially & Ethnically Minoritized Youths’ Varied Out-Of-School-Time Experiences and Their Effects on STEM Attitudes, Identity, and Career Interest (NSF Award #2215050).

PI and Co-PI Team: Philip Sadler, Remy Dou, Gerhard Sonnert, Susan Sunbury, and Monique Ross

“Our approach has been to position ourselves as learners and allies of their efforts. Even in our initial conversations with stakeholders from across these groups, we see the fruits of having centered their knowledge and understandings in order to bridge the research-practice divide.”

What inspired you to start this project?

Many groups have long been underrepresented in STEM careers. This is easily observed in college classrooms. To help remedy this situation, many educators develop and offer in-school or out-of-school courses, programs, and opportunities to increase student interest in STEM based on their own experience with youth who belong to groups traditionally underrepresented in STEM. Our team’s prior research shows a far greater influence of out-of-school-time (OST) experiences than in-school on the STEM career aspirations of underrepresented and marginalized students.

We have always been interested in the “return on investment” in such efforts, that is, what works best considering cost and duration. Independent of where and what programs are offered, there has been little evaluation of their effectiveness that is not conducted by those providing the offering. As expected, existing evaluations are rarely designed to be compared to one another or use sufficient controls to deal with student differences.

Our group is remedying this situation by employing epidemiological techniques to model the impact of structured activities designed to increase student interest in STEM careers. By surveying students in their first year of college, we can simultaneously test multiple hypotheses that represent program features (that may be common across several programs) while controlling for a host of background factors. To this end, the current project involves the design of a student survey with input from relevant stakeholders: students, program creators and implementors, and researchers in this area. Pilot-testing at colleges and universities that serve historically underrepresented students has helped validate and “de-bug” the instrument.

Our hope is that this project will culminate in a nationwide student survey to gauge exposure to, and the efficacy of, a wide range of traditional and new OST teaching practices and activities, adding to the knowledge-base on informal STEM education.

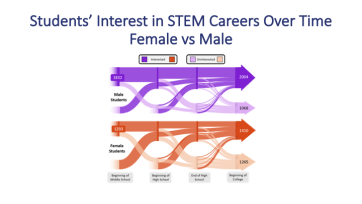

An example of data presented comparing student interest in STEM careers over time.

How did you conduct outreach with the communities you worked with?

At this stage in our project, we have primarily interacted with out-of-school time (OST) providers. We have used both interviews and surveys to get feedback from this group. We first interviewed select OST stakeholders across the nation, spanning the informal science education field, who have a vested interest in students underrepresented in STEM. We also recruited OST providers from institutions in cities with large communities traditionally underrepresented in STEM fields through informal science networks in an effort to engage a broad range of providers across multiple OST sectors. We asked them to take a brief survey to gain insight into how STEM is incorporated in their programs and to identify ideas that these stakeholders hold about which features of STEM programs have the greatest positive impact on participants’ STEM interest, identity, and their desire to pursue STEM careers and what barriers might exist for students traditionally underrepresented in STEM.

How did you build trust with the community members that you worked with?

One way we have built trust with OST providers was to introduce our team and our research to stakeholders and to demonstrate the potential impact of our research on their programs and on the broader informal science education field. During the early stages of this project, members of our team had the opportunity to attend several informal science education conferences such as the ASTC 2022 Annual Conference and the Annual meeting of NASA’s Science Activation Teams to make personal connections with OST practitioners who work with youth traditionally underrepresented in STEM. These organizations included The Franklin Institute, Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium, and the McWane Science Center. They engaged in conversations about issues of equity and culturally inclusive practices in OST education and how our research could address these issues. Many of these providers were later interviewed or surveyed. Another example was a workshop in which we presented our research findings to informal science professionals through the National Informal STEM Education Network (NISE Network). During the first half of the workshop, members of our team presented findings from a recent study How Pre-College Informal Activities Influence Female Participation in STEM Careers. This provided workshop participants with the opportunity to get to know our team and to learn about the types of data we collect and the analyses we can perform with this data. During the second half of the workshop, we introduced this project and asked for participants’ input about their experiences with culturally responsive OST activities, programs, and opportunities.

Did you get feedback from participants and community members? How did you incorporate this feedback into the project?

Yes, absolutely! Numerous hypotheses were generated by OST stakeholders. Responses from both interviews and surveys were used to create items for a survey, consisting of 29 multi-part questions asking students about their STEM interest, identity and career interest, their experiences in unstructured and structured OST activities, and their families’ interest and involvement in STEM, as well as barriers they have experienced participating in STEM activities and opportunities. The survey is currently being pilot-tested with over 1,000 first-year college students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Hispanic Serving Institutions.

Reflections

“The knowledge we generate is rooted in day-to-day, real-world practices…in doing so, we attend to the shared experiences of informal learning practitioners, including those experiences not currently centered within the research literature. “

What appeals to us about what we hope to accomplish is our projects’ aim to carry out research truly in service to practice. Our centering of hypotheses and accepted best practices drawn from the lived experiences of informal STEM learning practitioners and other stakeholders does just this. Across the country a tremendous amount of effort, commitment, and care is displayed everyday by informal learning educators, program developers, community leaders, and others who engage young people in STEM learning outside of school hours. Their work stands at the intersection of home-life and school-life, and it’s in those spaces that many of these stakeholders have developed, shared, and refined their approaches to fostering meaningful and equitable youth engagement. Many of those approaches attend to the very real, lived experiences of youth from socially and racially diverse communities. Yet, barriers exist that limit institutional capacity to learn from practitioners and leaders in ways that highlight their experiential strengths. Our project is designed to meet this need by providing some answers to questions shared by stakeholders across informal learning sectors, such as, “How much positive impact is our strategy having?”, “What can we build into our programs to design welcoming STEM learning experiences?”, “How could we better leverage our resources?”

By focusing on developing knowledge on the basis of what practitioners have learned about what works and doesn’t work for youth in local STEM ecosystems, and seeking to translate this knowledge to other communities and institutions, we believe our project will ultimately lead to meaningful impacts on the broader population of youth and specifically youth historically marginalized and/or minoritized in STEM related contexts. This is not only because the knowledge we generate is rooted in day-to-day, real-world practices, but also because in doing so, we attend to the shared experiences of informal learning practitioners, including those experiences not currently centered within the research literature. This project creates an opportunity to leverage the resources of our diverse team members in service to those practitioners.

Our ability to develop, test, and validate a survey to generate knowledge that broadly benefits practitioners and youth is predicated on entering into discourse with those two groups of stakeholders. This is something others wanting to carry out similar work may want to consider. It means leveraging existing partnerships to facilitate conversations with practitioners and youth, as well as proactively inviting conversations with new partners that have similar goals. We’re fortunate to carry out this project within an expansive community of informal learning practitioners and leaders who often seek to share their experiences so that others may benefit. This is also the case for the youth groups we engage with. Our approach has been to position ourselves as learners and allies of their efforts. Even in our initial conversations with stakeholders from across these groups, we see the fruits of having centered their knowledge and understandings in order to bridge the research-practice divide.